Battle of Stoke Field

| Battle of Stoke Field | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Wars of the Roses | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Henry VII Earl of Oxford Duke of Bedford Earl of Shrewsbury Baron Strange Baron Scales Sir John Savage |

Earl of Lincoln † Viscount Lovell Sir Thomas FitzGerald † Martin Schwartz † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,000 | 8,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 300–3,000 | 4,000 | ||||||

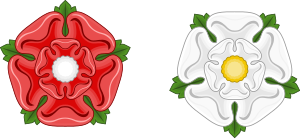

The Battle of Stoke Field on 16 June 1487 may be considered the last battle of the Wars of the Roses, since it was the last major engagement between contenders for the throne whose claims derived from descent from the houses of Lancaster and York. The Battle of Bosworth Field, two years previously, had established Henry VII on the throne, ending the last period of Yorkist rule and initiating that of the Tudors. The Battle of Stoke Field was the decisive engagement in an attempt by leading Yorkists to unseat the King in favour of the pretender Lambert Simnel.

Though it is often portrayed as almost a footnote to the major battles between York and Lancaster, it may have been slightly larger than Bosworth, with much heavier casualties, possibly because of the terrain which forced the two sides into close, attritional combat. In the end, though, Henry's victory was crushing. Almost all the leading Yorkists were killed in the battle.

Pretender

[edit]Henry VII of England held the throne for the new royal line (the House of Tudor), and had tried to gain the acceptance of the Yorkist faction by his marriage to their heiress, Elizabeth of York, but his hold on power was not entirely secure. The chief claimant of the York dynasty was the queen's first cousin, Edward, Earl of Warwick, the son of George, Duke of Clarence. This boy was kept confined in the Tower of London.[1]

An impostor claiming to be Edward (either Edward, Earl of Warwick, or Edward V, as Matthew Lewis hypothesises), whose name was Lambert Simnel, came to the attention of John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, through the agency of a priest called Richard Symonds.[2] Lincoln, although apparently reconciled with the Tudor king [citation needed], had a claim on the throne; the last Plantagenet, Richard III of England, had named Lincoln, his nephew, as the royal heir. Although he probably had no doubt about Simnel's true identity, Lincoln saw an opportunity for revenge and reparation.[1]

Lincoln fled the English court on 19 March 1487 and went to the court of Mechelen (Malines) and his aunt, Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy. Margaret provided financial and military support in the form of 2,000 German and Swiss mercenaries, under the commander Martin Schwartz. Lincoln was joined by a number of rebel English Lords at Mechelen, in particular Richard III's loyal supporter, Lord Lovell, Sir Richard Harleston, the former governor of Jersey and Thomas David, a captain of the English garrison at Calais. The Yorkists decided to sail to Ireland, where the Yorkist cause was popular, to gather more supporters.[3]

Yorkist rebellion

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

The Yorkist fleet set sail and arrived in Dublin on 4 May 1487. With the help of Gerald FitzGerald, 8th Earl of Kildare, and his brother Thomas FitzGerald of Laccagh, Lord Chancellor of Ireland, Lincoln recruited 4,500 Irish mercenaries, mostly kerns, lightly armoured but highly mobile infantry. With the support of the Irish nobility and clergy, Lincoln had the pretender Simnel crowned "King Edward VI" in Dublin on 24 May 1487.[4] Although a parliament was called for the new "king", Lincoln had no intention of remaining in Dublin and instead packed up the army and Simnel and set sail for north Lancashire.

On landing on 4 June 1487, Lincoln was joined by a number of the local gentry led by Sir Thomas Broughton. In a series of forced marches, the Yorkist army, now numbering some 8,000 men, covered over 200 miles in five days. On the night of 10 June, the Yorkists were camped at Bramham moor, and the pro-Tudor forces under Clifford were camped near Tadcaster. Lovell led 2,000 Yorkists on a night attack against Clifford's 400 men. The result was an overwhelming Yorkist victory.[5] Lincoln then outmanoeuvred King Henry's northern army, under the command of the Earl of Northumberland, by ordering a force under John, Lord Scrope, to mount a diversionary attack on Bootham Bar, York, on 12 June. Lord Scrope then withdrew northwards, taking Northumberland's army with him.

Lincoln and the main army continued southwards. Outside Doncaster, Lincoln encountered Lancastrian cavalry under Edward Woodville, Lord Scales. There followed three days of skirmishing through Sherwood Forest. Lincoln forced Scales back to Nottingham, where Scales' cavalry stayed to wait for the main royal army. However, the fighting had slowed down the Yorkist advance sufficiently to allow King Henry to receive substantial reinforcements under the command of Lord Strange by the time he joined Scales at Nottingham on 14 June. Rhys ap Thomas, Henry's leading supporter in Wales, also arrived with reinforcements.[6] Henry's army now outnumbered the Yorkists. In addition, it was "far better armed and equipped" than the Yorkist army.[6] His two principal military commanders, Jasper Tudor and John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford, were also more experienced than the Yorkist leaders.

Battle

[edit]On 15 June, King Henry began moving northeast toward Newark after receiving news that Lincoln had crossed the River Trent. Around nine in the morning of 16 June, King Henry's forward troops, commanded by the Earl of Oxford, encountered the Yorkist army assembled in a single block, on a brow of Rampire Hill surrounded on three sides by the River Trent at the village of East Stoke.[4] Their right flank was anchored on a high spot known as Burham Furlong.

Henry's army was divided into three battles, of which Oxford led the vanguard, he may have had as many as 6,000 infantry under his command, flanked by two wings of mounted troops under Baron Scales and Sir John Savage (both veterans of Bosworth).[7] As at Bosworth, the King left the direction of the fighting itself to Oxford.[8] Before the fight began some unusual lights in the sky were interpreted as ill-portents by Lancastrian soldiers, leading to some desertions, but Oxford and other nobles were able to restore morale, and soon the army was in "good array and in a fair battle".[9]

The Yorkists, arrayed in a single concentrated formation, were assaulted by arrows. Suffering from the missiles, they chose to surrender the high ground by immediately going on to the attack in the hope of breaking the Lancastrian line and rolling up the enemy army. Though outnumbered overall, the Yorkists had the advantage of a "core of well-trained foreign mercenaries",[8] and their concentrated force outnumbered Oxford's vanguard, which was the only part of the Lancastrian army engaged.

The vanguard was badly shaken, but Oxford was able to rally his force. The battle was bitterly contested for over three hours, but eventually sheer attrition told against the Yorkists after they failed to break the Lancastrian position early on. Henry chose not to commit his other "battles", leaving the struggle to the vanguard,[9] which was probably repeatedly reinforced as Lancastrian contingents came up, directed by Jasper Tudor. Though the German mercenaries were equipped with the latest handguns, the presence of large numbers of traditional archers in the Lancastrian army proved decisive. The skilled longbowmen were able to shoot volley after volley into the Yorkist position. The lack of body armour on the Irish troops in particular meant that they were cut down in increasing numbers by repeated showers of arrows.[8]

Unable to retreat (with the river on three sides), the German and Swiss mercenaries fought it out. According to Jean Molinet, by the end of the battle, they were "filled with arrows like hedgehogs".[10] The broken Yorkists fled towards the Trent down a ravine (known locally even today as the Red Gutter) in which many were cornered and killed.[4] Most of the Yorkist commanders—Lincoln, Fitzgerald, and Schwartz—fell fighting. Only Lord Lovell and Broughton may have escaped. Lovell disappeared after the battle and was never seen again. He may have gone to Scotland, as there is evidence of a safe conduct pass being granted him there, but his later fate is unknown.[11] In the 18th century a body was found inside a secret room at his house, Minster Lovell Hall in Minster Lovell, Oxfordshire, leading to conjecture that it was his.[12]

Aftermath

[edit]Simnel was captured, but was pardoned by Henry in a gesture of clemency which did his reputation no harm. Henry realised that Simnel was merely a puppet for the leading Yorkists. He was given a job in the royal kitchen as a spit-turner, and later promoted to falconer. The Irish nobles who had supported Simnel were also pardoned, as Henry believed he needed their support to govern Ireland effectively. However, Henry later persuaded the Pope to excommunicate the Irish clergy who had supported the rebellion.[6] Two other Yorkist conspirators were also captured: Richard Symonds and John Payne, Bishop of Meath. Symonds was the man who had introduced Lincoln to Simnel; Payne had preached the sermon at Simnel's coronation. Neither was executed: Symonds was imprisoned, and Payne was pardoned and eventually restored to royal favour.[6]

To mark his victory, Henry raised his standard on Burham Furlong. The spot is marked by a large stone memorial with the legend "Here stood the Burrand Bush planted on the spot where Henry VII placed his standard after the Battle of Stoke 16 June 1487".[13] Henry knighted many of his supporters in the aftermath of the battle. A handwritten list of the new knights by John Writhe survives inserted into a copy of the book Game and Play of Chess.[14] Thirteen new bannerets were created and fifty-two men were knighted. The following year in 1488 the two main cavalry commanders of Henry's army, Baron Scales and Sir John Savage, were both made Knights of the Garter.

Henry had hoped to capture Lincoln alive in order to learn from him the true extent of support for the Yorkists. Instead, Henry launched a series of enquiries, the outcome of which was "relatively few executions and very many fines", consistent with Henry's policy of controlling the aristocracy by weakening it financially. After the battle, he progressed north through Pontefract, York, Durham, and Newcastle to show himself in those areas that had been strongholds of Richard III's supporters.[15] Later in Henry's reign, in the 1490s, another pretender to the throne emerged, in the person of Perkin Warbeck; this time the matter was resolved without having to fight a battle, in the Second Cornish uprising of 1497.

Missing Princes Project

[edit]In 2022, Langley led "The Missing Princes Project" to discover the fate of the Princes in the Tower.[16][17][18] The project began in 2015, following the reburial of Richard III in Leicester and was formally launched in July the following year.[19] In 2023 she claimed to have discovered new evidence that disproved the theory that Richard III was responsible for the deaths of the princes. Along with Rob Rinder, she hosted a Channel 4 programme called Princes in the Tower: The New Evidence, in which she revealed her own theories and new archival discoveries. [20][21] Although praising Langley's discoveries, The Spectator's reviewer called the programme "a calculated insult to the viewer";[22] The Times called it "compelling" and awarded the documentary its "Critics Choice."[23] The programme achieved a large audience [24] with Richard III and the Princes in the Tower trending on Twitter / X. The Richard III Society issued a press release stating:

The disappearance of the princes has always been described as a great unsolved mystery. Why? Because there was no evidence of their fate. Their murder was never more than conjecture, but it was put about by the authorities and – for safety’s sake – only the brave dared to think differently. From now on, history must take account of this new breakthrough evidence. No longer can anyone confidently claim the princes were killed by Richard III.[25]

Three leading members of the Dutch Research Group who had assisted in the project subsequently distanced themselves from Langley's documentary and book, arguing that the documents they had discovered "are in our own opinion open to various interpretations and do not constitute irrefutable proof" for the survival of the princes.[26] Langley responded that her conclusions were based on "the totality of evidence thus assembled and the outcomes of a modern police missing person investigation methodology ... (and not through a traditional historical research method)".[27] Historian Michael Hicks similarly opined that the new documents "do add to knowledge of the Tudor impostors, but they fall short of proof that either Edward V or Richard Duke of York survived beyond their disappearance in the autumn of 1483".[28] Langley again responded that her use of "police investigative methodology" had provided "sufficient reason to conclude" that the two had survived the reign of Richard III.[29]

Bibliography

[edit]- Bennett, Michael J. (1987). Lambert Simnel and the Battle of Stoke. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-3120-1213-7. OL 2385722M.

- Mackie, John Duncan (1994) [1952]. The earlier Tudors: 1485–1558. Oxford history of England. Vol. 7. Oxford University Press. pp. 73–75. ISBN 0-1928-5292-2.

- Roberts, David E. (1987). The Battle of Stoke Field 1487. Keljham: Newark & Sherwood District Council. OCLC 942845028.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b James A. Williamson, The Tudor Age, D. McKay Co., 1961, p. 26

- ^ Lewis, Matthew (11 September 2017). The Survival of the Princes in the Tower: Murder, Mystery and Myth. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-8528-4.

- ^ Siobhán Kilfeather, Dublin: A Cultural History, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 37

- ^ a b c Castelow, Ellen. "The Battle of Stoke Field", History Magazine

- ^ Baldwin, David (2006). Stoke Field, the last battle of the Wars of the Roses. Pen and Sword. pp. 42–43. ISBN 1-84415-166-2.

- ^ a b c d Van Cleve Alexander, Michael, The First of the Tudors: A Study of Henry VII and His Reign, Taylor & Francis, 1981, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Baldwin, D. Stoke Field: The Last Battle of the Wars of the Roses [page needed]

- ^ a b c Pendrill, Colin, The Wars of the Roses and Henry VII: Turbulence, Tyranny and Tradition in England 1459 – c. 1513, Heinemann, 2004, p. 101.

- ^ a b Ross, James, John De Vere, Thirteenth Earl of Oxford (1442–1513): The Foremost Man of the Kingdom, Boydell Press, 2011, p. 118.

- ^ G. W. Bernard, The Tudor Nobility, Manchester University Press, 1992, p. 92.

- ^ Horrox, Rosemary. "Lovell, Francis". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ James A. Williamson, The Tudor Age, D. McKay, New York, 1961, p. 27.

- ^ Haigh, Philip A. 1995. The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses. Stroud, Gloucestershire. Allan Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7509-0904-8

- ^ Anne Payne, "Sir Thomas Wriothesley and his Heraldic Artists", Brown & McKendrick (eds), Illuminating the Book: Makers and Interpreters: Essays in Honour of Janet Backhouse., British Library, London, 1998, p. 159

- ^ Mackie, J.D., The Earlier Tudors: 1485–1558, Oxford University Press, 1959, p. 72.

- ^ Dunne, Daisy (29 December 2021). "History's greatest whodunnit would be ruined if we solved it, Philippa Langley team findings". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

A team led by Philippa Langley, who found the skeleton of King Richard III under a car park in 2012, have uncovered what they believe to be clues to the survival of Edward V in the Devon village of Coldridge....

- ^ Catling, Chris (22 November 2022). "From the Princes in the Tower to Northumbria's Golden Age". The Past. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ "Missing Princes Project". Philippa Langley. 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ Langley, Philippa (2023). The Princes in the Tower: Solving History's Greatest Cold Case. Cheltenham: The History Press. p. 26. ISBN 9781803995410.

- ^ Lee Garrett (17 November 2023). "Historian says Richard III did not kill Princes in the Tower in 'landmark' Channel 4 show". Leicester Mercury. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ The Princes in the Tower: The New Evidence Channel 4 Saturday 18 November. Retrieved 20 May 2024. https://www.channel4.com/programmes/the-princes-in-the-tower-the-new-evidence The Princes in the Tower PBS 22 November 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2024. https://www.pbs.org/wnet/secrets/preview-the-princes-in-the-tower-ybnnnv/7943/

- ^ James Delingpole (22 November 2023). "A calculated insult to the viewer: Channel 4's The Princes in the Tower – The New Evidence reviewed". The Spectator. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ The Times, Review, Saturday 18 November 2023, p.20. Image only, see: [WIKI LANGLEY PRINCES DOC_ THETIMES CRITICS CHOICE_18 NOV 2023.jpg]

- ^ The Princes in the Tower: The New Evidence Brinkworth Productions. Retrieved 20 May 2024. https://www.brinkworth.tv/shows/the-princes-in-the-tower-the-new-evidence/

- ^ "Princes in the Tower – History is Being Rewritten" (PDF) (Press release). Richard III Society. 16 November 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Maula, Zoë; Roefstra, Jean; Wiss, William (June 2024). "Dutch statement on The Missing Princes Project". The Ricardian Bulletin. p. 4.

- ^ Langley, Philippa (June 2024). "A reply from Philippa Langley". The Ricardian Bulletin. p. 4.

- ^ Hicks, Michael (June 2024). "More proof needed on Princes". The Ricardian Bulletin. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Langley, Philippa (June 2024). "In response to Michael Hicks". The Ricardian Bulletin. p. 5.