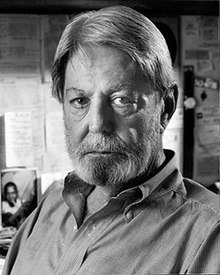

Shelby Foote

Shelby Foote | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Shelby Dade Foote, Jr. November 17, 1916 Greenville, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | June 27, 2005 (aged 88) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Alma mater | University of North Carolina Chapel Hill |

| Subjects | American Civil War |

| Notable works | The Civil War: A Narrative |

| Spouse | Tess Lavery

(m. 1944; div. 1946)Marguerite "Peggy" Desommes

(m. 1948; div. 1952)Gwyn Rainer (m. 1956) |

| Children | 2 |

Shelby Dade Foote Jr. (November 17, 1916 – June 27, 2005) was an American writer, historian and journalist.[1] Although he primarily viewed himself as a novelist, he is now best known for his authorship of The Civil War: A Narrative, a three-volume history of the American Civil War.[2]

With geographic and cultural roots in the Mississippi Delta, Foote's life and writing paralleled the radical shift from the agrarian planter system of the Old South to the Civil Rights era of the New South. Foote was little known to the general public until his appearance in Ken Burns's PBS documentary The Civil War in 1990, where he introduced a generation of Americans to a war that he believed was "central to all our lives".[3] Foote did all his writing by hand with a nib pen, later transcribing the result into a typewritten copy.[4][5] While Foote's work was mostly well-received during his lifetime, it has been criticized by professional historians and academics in the 21st century.[6][7][8]

Early life

[edit]Foote was born in Greenville, Mississippi, the son of Shelby Dade Foote and his wife Lillian (née Rosenstock). Foote's paternal grandfather, Huger Lee Foote (1854–1915) was a planter who gambled away most of his assets. His paternal great-grandfather was Hezekiah William Foote (1813–99), an American Confederate veteran, attorney, planter and politician from Mississippi.[9] His maternal grandfather was a Jewish immigrant from Vienna.

Foote was raised in his father's Episcopal faith. He also attended synagogue each Saturday with his mother until the age of eleven.[10]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Foote moved frequently as his father was promoted within the Armour and Company, living in Greenville, Jackson, and Vicksburg, Mississippi; Pensacola, Florida; and Mobile, Alabama. When Foote was five, his father died in Mobile, and his mother moved them back to Greenville.[11] When Foote was 15 years old, he began lifelong friendships with Walker Percy and his brothers. Foote and Percy influenced each other greatly. Additional influences on Foote's writing were Tacitus, Thucydides, Gibbon and Proust.[12]

Foote misremembered Greenville as different from Southern stereotypes, "There was never a lynching in Greenville; it never got swept off its feet that way. The Ku Klux Klan never made any headway, at a time when it was making headway almost everywhere else."[13] In fact, there was a lynching in Greenville in 1903, and the Equal Justice Initiative has found 13 lynchings in the county between 1877 and 1950.[14][15][16][17]

At Greenville High School, Foote edited the student newspaper, The Pica, and frequently used it to lampoon the school's principal. The principal got his revenge by recommending University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill not admit Foote in 1935. Foote was only able to get in by passing a round of admission tests.[11]

In 1936, he was initiated in the Alpha Delta chapter of the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity. Foote often skipped class to explore the library, even spending a night among the shelves. He began contributing pieces of fiction to Carolina Magazine, UNC's award-winning literary journal.[11] Foote returned to Greenville in 1937, where he worked in construction and for a local newspaper Delta Democrat Times. Foote's Jewish heritage led to discrimination at Chapel Hill, an experience that bolstered his later support for the Civil Rights Movement.[8]: 17

In 1940, Foote joined the Mississippi National Guard and was commissioned as captain of artillery. His battalion was deployed to Northern Ireland in 1943. The following year, Foote was court-martialed and dismissed from the service. He was charged with falsifying a government document relating to the check-in of a vehicle he borrowed to visit his girlfriend in Belfast.

Foote got a job with the Associated Press in New York City. In January 1945, he enlisted in the United States Marine Corps but was discharged as a private in November 1945 without seeing combat.[11]

Foote returned to Greenville and took a job with a local radio station. He spent most of his time writing and submitted part of his first novel to The Saturday Evening Post. When the Post published "Flood Burial" in 1946, Foote earned $750 and quit his job to write full-time.[11]

Novels

[edit]Foote's first novel, Tournament (1949), was inspired by his planter grandfather, who died two years before the author's birth. For his next novel, Follow Me Down (1950), Foote drew on the proceedings of a Greenville murder trial he attended in 1941.[11] Love in a Dry Season (1951) was his attempt to deal with the "upper classes of the Mississippi Delta" around the time of the Great Depression. Foote often expressed great affection for this novel.[3]

In Shiloh (1952), Foote developed his use of historical narrative to tell the story of the bloodiest battle in American history to that point. The narrative is presented by 17 characters: Confederate soldiers Metcalf, Dade, and Polly; and Union soldiers Fountain, Flickner, with each of the twelve named soldiers in the Indiana squad given one section of that chapter. The novel quickly sold 6,000 copies and was praised by critics. The book does showcase Foote's Southern chauvinism, as the author "favored the South throughout the novel, portraying the Confederate cause as a fight for constitutional liberty and omitting any reference to slavery".[8]: 15–6

Jordan County: A Landscape in Narrative (1954) is a collection of novellas, short stories, and sketches from Foote's mythical Mississippi county.[3]

September, September (1978) is the story of three white Southerners who kidnap the 8-year-old son of a wealthy African American, told against the backdrop of Memphis in September 1957. Foote struggled to write realistic African-American characters. He avoided including them in his work until September, September (1978). Writing black characters for the novel "scared the hell out of" him, and he particularly struggled with the novel's wealthy Theo Wiggins. Foote told Walker Percy the character was one of "those bourgeois negroes, and I never really knew a single bourgeois nigger in my life."[11]: 227

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Although he was not one of America's best-known fiction writers, Foote was admired by peers like Eudora Welty and his literary hero William Faulkner. The latter once told a University of Virginia class that Foote "shows promise, if he'll just stop trying to write Faulkner, and will write some Shelby Foote."[11] Foote's fiction was recommended by both The New Yorker and critics from The New York Times Book Review.[3]

History

[edit]Foote moved to Memphis in 1952. He worked on an epic called Two Gates to the City that he had begun outlining in 1951. He was struggling with the "dark, horrible novel" when Bennett Cerf of Random House asked Foote to write a short history of the Civil War. Cerf was impressed with the factual accuracy and rich detail of Shiloh, and he wanted to capitalize on the centenary of the war. Cerf offered him a contract for a work of approximately 200,000 words.[11]

Foote worked for several weeks on an outline and decided that Cerf's specifications were too small. He requested the project be expanded to three volumes of 5–600,000 words each. He estimated it would take nine years.[11] It took twenty. The finished work ran to 3000 pages and was titled The Civil War: A Narrative. The individual volumes are Fort Sumter to Perryville (1958), Fredericksburg to Meridian (1963), and Red River to Appomattox (1974).

Foote had no training as a historian. He visited battlefields and read widely: standard biographies, campaign studies, and recent books by Hudson Strode, Bruce Catton, James G. Randall, Clifford Dowdey, T. Harry Williams, Kenneth M. Stampp and Allan Nevins.[18] He also mined the primary sources in the 128-volume Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. He developed new respect for such disparate figures as Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, Patrick Cleburne, Edwin Stanton and Jefferson Davis. By contrast, he grew to dislike such figures as Phil Sheridan and Joe Johnston.[3]: 141

Foote described himself as a "novelist-historian" who employed "the historian’s standards without his paraphernalia" and "employed the novelist’s methods without his license."[8]: 17 [19]: 21 To heighten the storytelling of his book, Foote eschewed footnotes.[19]: 25 Citations would have "totally shattered what I was doing. I didn't want people glancing down at the bottom of the page every other sentence". Foote concluded most historians are "so concerned with finding out what happened that they make the enormous mistake of equating facts with truth...you can't get the truth from facts. The truth is the way you feel about it".[2]

During the project, Foote lived off two Guggenheim Fellowships (1955–1960), Ford Foundation grants, and loans from Walker Percy.[3][11]

Reception

[edit]Many reviews of The Civil War: A Narrative praised its style. Southern historian C. Vann Woodward argued Foote's work was acceptable "narrative history," which "nonprofessionals have all but taken over."

The gradual withering of the narrative impulse in favor of the analytical urge among professional academic historians has resulted in a virtual abdication of the oldest and most honored role of the historian, that of storyteller. Having abdicated... the professional is in a poor position to patronize amateurs who fulfill the needed function he has abandoned...In no field is the abdication of the professionals more evident than in military history, the strictly martial, guns-and-battle aspect of war, the most essential aspect.[20]

Foote was criticized for his lack of interest in more current historical research, and for a less firm grasp of politics than military affairs.[21] John F. Marszalek praised Foote's grasp of military history, "Twenty years of dedicated labor have resulted in a literary masterpiece which places Shelby Foote among those very few historians who are authors of major syntheses...this history will long stand with the volumes of Bruce Catton as the final word on the military history of the Civil War."[22]

In 1993, Richard N. Current argued that Foote too often depended on a single source for lifelike details, but "probably is as accurate as most historians...Foote's monumental narrative most likely will continue to be read and remembered as a classic of its kind."[23] Academic historians routinely lament Foote's lack of citations.[24]

Eric Foner and Leon Litwack felt Foote underplayed the extent of Southern white racism, treating "white southerners" as synonymous with all "southerners." Litwack concluded that "Foote is an engaging battlefield guide, a master of the anecdote, and a gifted and charming story teller, but he is not a good historian."[25] Foote's biographer concluded, "at its best, Foote's writing dramatised tensions related to racial and regional identity. At its worst, it fell back on the social prescriptions of Southern paternalism."[11]: xix

Lost Cause

[edit]Many critics read Foote as sympathetic to the Lost Cause of the Confederacy fallacy.[11]: xix, 69 [8] He relied extensively on the work of Hudson Strode, whose sympathy for Lost Cause claims resulted in a portrait of Jefferson Davis as a tragic hero without many of the flaws attributed to him by other historians."[21] Annette Gordon-Reed suggested Foote's work is powered by romantic nostalgia and bears "the very strong mark of memory as opposed to history...the memories of that war which grew up with many white Southern males of his generation, are what power the narrative."[8]

Chandra Manning has suggested that Foote belongs to a school of Civil War historiography that "answers 'where does slavery fit in the Union cause' by saying 'nowhere,' except maybe in the most reluctant and instrumental way".[26] Joshua M. Zeitz described Foote as "living proof that many Americans—especially those who are most interested in the Civil War—remain under the spell of a century-old tendency to mystify the Confederacy's martial glory at the expense of recalling the intense ideological purpose associated with its cause...[Foote is] living testimony to the failure of many Civil War enthusiasts and public figures to disavow the American army that fought under the rebel banner. As a nation, we remain very much under the spell of Robert E. Lee, even as we decry slavery and its legacy".[27]

In a 1997 interview, Foote stated that he would have fought for the Confederacy, "What's more, I would fight for the Confederacy today if the circumstances were similar...States' rights is not just a theoretical excuse for oppressing people. You have to understand that the raggedy Confederate soldier who owned no slaves and probably couldn't even read the Constitution, let alone understand it, when he was captured by Union soldiers and asked, 'What are you fighting for?' replied, 'I'm fighting because you're down here.' So I certainly would have fought to keep people from invading my native state."[28]

Foote saw slavery as a cause of the Civil War, commenting that "the people who say slavery had nothing to do with the war are just as wrong as the people who say it had everything to do with the war." He argued slavery was "doomed to extinction" and was used as "propaganda".[29] He insisted, "no soldier on either side gave a damn about the slaves—they were fighting for other reasons entirely in their minds."[8]

Praise of Nathan Bedford Forrest

[edit]Foote kept Nathan Bedford Forrest's portrait on his wall and lauded him as "one of the most attractive men who ever walked through the pages of history". He dismissed Forrest's role in the Fort Pillow Massacre.[28][30] He suggested the general had tried to prevent the massacre, despite evidence to the contrary. Foote also compared Forrest to John Keats and Abraham Lincoln[29][31]

Foote argued, "the French Maquis did far worse things than the Ku Klux Klan ever did—who never blew up trains or burnt bridges or anything else," and that the First Klan "didn't even have lynchings."[28]

Civil War historian Harold Holzer dismissed Foote's characterization of Forrest as "one of the great geniuses of the war" along with Lincoln, "Ken Burns always looks for varied voices and...characters, and Shelby Foote was certainly a character...Foote somehow compared the great emancipator with a man who owned slaves, murdered blacks and joined the Ku Klux Klan."[7]

Views

[edit]Foote was staunchly anti-slavery, and believed that emancipation was insufficient to address historical wrongs done to African-Americans: "The institution of slavery is a stain on this nation's soul that will never be cleansed. It is just as wrong as wrong can be, a huge sin...There's a second sin that's almost as great and that's emancipation...There should have been a huge program for schools. There should have been all kinds of employment provided for them. Not modern welfare, you can't expect that in the middle of the nineteenth century, but there should have been some earnest effort to prepare these people for citizenship. They were not prepared, and operated under horrible disadvantages once the army was withdrawn, and some of the consequences are very much with us today." Foote condemned the Freedmen's Bureau, which "did, perhaps, some good work, but it was mostly a joke, corrupt in all kinds of ways."[30]

While writing his history of the war in the 1950s and 1960s, Foote was a liberal on racial issues. He supported school integration, opposed Eisenhower's hands-off approach to Southern racism and openly championed Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Foote protested against the KKK's use of the Confederate flag, believing 'that everything they stood for was almost exactly the opposite of everything the Confederacy had stood for'.[11]: xix, 185–6, 201–2 Foote was an outspoken supporter of the Civil Rights Movement in the South, arguing in 1968 that "the main problem facing the white, upper-class South is to decide whether or not the negro is a man...if he is a man, as of course he is, then the negro is entitled to the respect an honorable man will automatically feel to an equal."[8]

Foote retained complex, patriarchal and sympathetic views of African Americans and race relations. Foote continued to develop his perception of the travesties that befell blacks in Southern life, a culture that he would later call "perhaps the most racist society in the United States."[11]: 226, 64

Foote believed his knowledge of the South meant he understood African-Americans like Nat Turner better than Northern African-American intellectuals, "I think that I am closer to Nat Turner than James Baldwin is...I consider somebody out of Harlem to be very different from someone out of Tidewater Virginia".[32]

In 1986, Foote strongly denounced the NAACP's campaign to remove the Nathan Bedford Forrest Monument in Memphis, "the day that black people admire Forrest as much as I do is the day when they will be free and equal, for they will have gotten prejudice out of their minds as we whites are trying to get it out of ours."[8]: 22 Foote argued in favor of "the Confederate flag flying anywhere anybody wants to fly it at any time...the flag to me represents many noble things."[33]

Speaking in 1989, Foote stated that "this black separatist movement is a bunch of junk", believing that African-Americans should model themselves on Jews, who Foote believed had a talent for making money. Foote, however, believed "the odds against" black people were to be "too great" for them to succeed in the US, as a result of "having a different color skin". Foote maintained that the KKK of the 1920s was "mostly anti-Catholic, incidentally anti-Semitic and really was not much concerned about the Negro".[3]: 37, 46

Later life

[edit]After finishing September, September, Foote resumed work on Two Gates to the City, the novel he had set aside in 1954 to write the Civil War trilogy. The work still gave him trouble and he set it aside once more, in the summer of 1978, to write "Echoes of Shiloh," an article for National Geographic Magazine. By 1981, he had given up on Two Gates altogether, though he told interviewers for years afterward that he continued to work on it.[11] He served on the Naval Academy Advisory Board in the 1980s.[34]

In the late 1980s, Ken Burns had assembled a group of consultants to interview for his Civil War documentary. Foote was not in this initial group, though Burns had Foote's trilogy on his reading list. A phone call from Robert Penn Warren prompted Burns to contact Foote. Burns and crew traveled to Memphis in 1986 to film an interview with Foote in the anteroom of his study. In November 1986, Foote figured prominently at a meeting of dozens of consultants gathered to critique Burns' script. Burns interviewed Foote on-camera in Memphis and Vicksburg in 1987. That same year, he became a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. The Civil War historian Judkin Browning has noted that Foote's outspoken praise of Nathan Bedford Forrest in the documentary ensured "Lost Causers raised their beer mugs in salute while historians hurled their lagers at their televisions."[35] Foote has been further criticized for repeating "plainly wrong" Lost Cause tropes in his commentary, particularly over the issue of apparently "overwhelming" Northern industrial advantage and his downplaying of the role of slavery in causing the Civil War.[29]

The extent of Foote's apparent apologia for white Southern racism and Lost Cause mythologizing was satirized in the character of Sherman Hoyle in the 2004 mockumentary C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America, a character defined by his "consistent lamenting of and apologies for the good ole days."[36]

Foote professed to be a reluctant celebrity. When The Civil War was first broadcast, his telephone number was publicly listed and he received many phone calls from people who had seen him on television. Foote never unlisted his number, and the volume of calls increased each time the series re-aired.[11] Many Memphis natives were known to pay Foote a visit at his East Parkway residence in Midtown Memphis.

Horton Foote, the playwright and screenwriter (To Kill A Mockingbird, Baby the Rain Must Fall and Tender Mercies) was the voice of Jefferson Davis in the PBS series. The two Footes are third cousins; their great-grandfathers were brothers. "And while we didn't grow up together, we have become friends; I was the voice of Jefferson Davis in that TV series", Horton Foote added proudly.[37]

In 1992, Foote received an honorary doctorate from the University of North Carolina. In the early 1990s, Foote was interviewed by journalist Tony Horwitz for the project on American memory of the Civil War which Horwitz eventually published as Confederates in the Attic (1998). Foote was also a member of The Modern Library's editorial board for the re-launch of the series in the mid-1990s, this series published two books excerpted from his Civil War narrative. Foote also contributed a long introduction to their edition of Stephen Crane's The Red Badge of Courage, giving a narrative biography of the author. He also received the 1992 St. Louis Literary Award from the Saint Louis University Library Associates.[38][39]

Foote was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1994. Also in 1994, Foote joined Protect Historic America and was instrumental in opposing a Disney theme park near battlefield sites in Virginia.[11] Along the way, Burns asked him to return for his upcoming documentary Baseball, where he appeared in both the 2nd Inning discussing his recollections of the dynamics of the crowds in his youth and in the 5th Inning (TV series), where he gave an account of his meeting Babe Ruth.

In 1998, the author Tony Horwitz visited Foote for his book Confederates in the Attic, a meeting in which Foote declared he was "dismayed" by the "behavior of blacks, who are fulfilling every dire prophesy the Ku Klux Klan made", and that African Americans were "acting as if the utter lie about blacks being somewhere between ape and man were true".[40] Foote emphasized that his loyalties during the 1860s would have been to Southerners: "I’d be with my people, right or wrong."[41] Foote also argued that freedmen had led to the failure of Reconstruction and that the Confederate flag represented "law, honour, love of country."[41] Foote stated that he would have been willing to fight for the Confederacy: "If I was against slavery, I'd still be with the South. I'm a man, my society needs me, here I am."[27]

In 1999, Foote received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement and an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from The College of William & Mary. [42] [43]

On September 2, 2001, he was the focus of the C-SPAN television program In-Depth. In a three-hour interview, conducted by C-SPAN founder Brian Lamb, Foote shows off the library of his home, working room, and writing desk, and details the writing of his books as well as taking on-air calls and emails.[44]

Foote campaigned in the 2001 referendum on the Flag of Mississippi, arguing against a proposal which would have replaced the Confederate battle flag with a blue canton with 20 stars.[45] Foote rejected the Confederate flag's association with white supremacy and argued "I’m for the Confederate flag always and forever. Many among the finest people this country has ever produced died in that war. To take it and call it a symbol of evil is a misrepresentation."[46]

In 2003, Foote received the Peggy V. Helmerich Distinguished Author Award. The Helmerich Award is presented annually by the Tulsa Library Trust.

Foote died at Baptist Hospital in Memphis on June 27, 2005, aged 88. He had had a heart attack after a recent pulmonary embolism.[47] He was interred in Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis. His grave is beside the family plot of General Forrest.[48]

Legacy

[edit]In a 2011 commentary, Ta-Nehisi Coates concluded the work was not a "neo-Confederate apologia", but he lamented Foote's lack of a Black perspective: "Shelby Foote wrote The Civil War, but he never understood it. Understanding the Civil War was a luxury his whiteness could ill-afford."[49]

In 2013, the Sons of Confederate Veterans protested the removal of Nathan Bedford Forrest's statue in Memphis by invoking Foote's characterization of him as a "humane slave holder".[50]

In 2017, the conservative writer Bill Kauffman, writing in The American Conservative, argued for a revival of Foote's sympathetic portrayal of the South.[33] In October 2017, John F. Kelly, the White House Chief of Staff for President Donald Trump, argued that "the lack of ability to compromise led to the Civil War" and praised Robert E. Lee as an "honorable man".[51] White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders defended Kelly's controversial remarks by citing Foote's work.[52]

On October 18, 2019, a Mississippi Writers Trail historical marker was installed in Greenville, Mississippi, to honor the literary and historical contributions of Shelby Foote.[53]

Foote's distinctive Southern accent was the model for Daniel Craig's character in the 2019 film Knives Out.[54]

Publications

[edit]Fiction

[edit]- Tournament (1949)

- Follow Me Down (1950)

- Love in a Dry Season (1951)

- Shiloh: A Novel (1952)

- Jordan County: A Landscape in Narrative (1954)

- September, September (1978)

- The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol 1: Fort Sumter to Perryville (1958)

- The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol 2: Fredericksburg to Meridian (1963)

- The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol 3: Red River to Appomattox (1974)

Titles excerpted from The Civil War: A Narrative

[edit]- Stars in Their Courses: The Gettysburg Campaign, June–July 1863

- The Beleaguered City: The Vicksburg Campaign, December 1862 – July 1863

These two books published by the Modern Library are excerpted from the three-volume narrative. The former was a whole chapter in the second volume, and the latter excerpted from the second volume where some material was interspersed with other events. Both were also presented as unabridged audio books read by the author.

Other

[edit]- Foote edited a modern edition of Chickamauga And Other Civil War Stories (previously published as The Night Before Chancellorsville And Other Civil War Stories), an anthology of Civil War stories by various authors.

- Foote contributed a lengthy introduction to the 1993 Modern Library edition of Stephen Crane's The Red Badge of Courage (which was published along with "The Veteran", a short story that features the hero of the larger work at the end of his life). In this introduction, Foote recounts the biography of Crane in the same narrative style as Foote's Civil War work.

- Foote collaborated with his wife's cousin, photographer Nell Dickerson, to produce the book Gone: A Photographic Plea for Preservation. Dickerson used Foote's story "Pillar of Fire", from his 1954 novel Jordan County: A Landscape in Narrative, as the text to illustrate her photographs of southern antebellum buildings in ruins.

References

[edit]- ^ Keri Leigh, Merritt. "Why We Need a New Civil War Documentary". Smithsonian. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Mackowski, C (ed.) 2020, Entertaining History : The Civil War in Literature, Film, and Song, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale, p.58–61.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carter, William C. (1989). Conversations with Shelby Foote. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 0-87805-385-9.

- ^ "MWP Writer News (June 28, 2005): Shelby Foote dies at 88". Olemiss.edu. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ "At 37:02 Shelby describes what he does after writing by hand". C-SPAN. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ Brockell, Gillian (September 26, 2020). "Re-watching 'The Civil War' During the Breonna Taylor and George Floyd Protests". Analysis. The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

- ^ a b Italie, Hillel (November 4, 2017). "Debate over Ken Burns Civil War Doc Continues Over Decades". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Huebner, Timothy S.; McGrady, Madeleine M. (Winter 2015). "Shelby Foote, Memphis, and the Civil War in American Memory". Southern Cultures. 21 (4): 25. doi:10.1353/scu.2015.0044. JSTOR 26220240. S2CID 147664153.

- ^ Jones, John Griffin (July 16, 1982). Mississippi Writers Talking: Interviews with Eudora Welty, Shelby Foote, Elizabeth Spencer, Barry Hannah, Beth Henley. University Press of Mississippi. p. 39. ISBN 9780878051540. Retrieved July 16, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The American Enterprise: Shelby Foote". Archived from the original on February 13, 2005. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Chapman, Stuart (2003), Shelby Foote: A Writer's Life, Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 1-57806-359-0

- ^ "Shelby Foote, Historian and Novelist, Dies at 88", The New York Times, June 29, 2005

- ^ Tillinghast, Richard, and Shelby Foote. “An Interview with Shelby Foote.” Ploughshares, vol. 9, no. 2/3, 1983, 120

- ^ Hines, Mary (January 1, 1992). "Death at the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Geography of Lynching in the Deep South, 1882 to 1910". LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. doi:10.31390/gradschool_disstheses.5384. S2CID 135433861. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ "LYNCHING IN MISSISSIPPI; Negro Who Attacked Telephone Girl Taken from Jail and Hanged from Telephone Pole". The New York Times. June 5, 1903. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ "Personal". Daily Public Ledger. June 9, 1903. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

John Dennis, a Negro, attempted an assault on a white woman near Greenville, Miss., June 2d, and was lynched June 4th.

- ^ Stewart Emory Tolnay; E. M. Beck (1995). A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882-1930. University of Illinois Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-252-06413-5.

- ^ Shelby Foote, "Bibliographical note" in Red River to Appomattox (1974) pp 1063–1064.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Douglas. "'The Conflict Is behind Me Now": Shelby Foote Writes the Civil War." The Southern Literary Journal, vol. 36, no. 1, 2003.

- ^ Woodward, C. Vann. "The Great American Butchery," New York Review of Books (March 6, 1975).

- ^ a b Barr, Alwyn. “The Journal of Southern History.” The Journal of Southern History, vol. 41, no. 3, 1975, pp. 418–419.

- ^ John F. Marszalek, "The Civil War, A Narrative: Red River to Appomattox: Review," Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine (April 1976) 59#2 pp 223-225.

- ^ Richard N, Current, "Review", Journal of Southern History (Aug 1993) 59#3 p. 595.

- ^ James I. Robertson Jr. "The Civil War: A Narrative (review)" Civil War History, Volume 21, Number 2, June 1975, pp. 172-175

- ^ Renda, Lex (August 26, 1996). "Review of Toplin, Robert Brent, ed., Ken Burns's The Civil War: Historians Respond". H-net.org. H-CivWar, H-Review. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Chandra Manning. "All for the Union...and Emancipation, too: What the Civil War Was About" Dissent, Volume 59, Number 1, Winter 2012, 93

- ^ a b Zeitz, Joshua Michael "Rebel redemption redux" Dissent; Philadelphia Vol. 48, Iss. 1, (Winter 2001): 70-77.

- ^ a b c Carter Coleman, Donald Faulkner, and William Kennedy. Shelby Foote, The Art of Fiction No. 158. The Paris Review Issue 151, Summer 1999

- ^ a b c Sharrett, Christopher. “Reconciliation and the Politics of Forgetting: Notes on Civil War Documentaries.” Cinéaste, vol. 36, no. 4, 2011, pp. 27

- ^ a b Interviewed by Carter Coleman; Donald Faulkner; William Kennedy (October 26, 1999). "The Art of Fiction No. 158". Theparisreview.org. Vol. Summer 1999, no. 151. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ^ Court Carney, "The Contested Image of Nathan Bedford Forrest." Journal of Southern History 67.3 (2001): 601-630 online.

- ^ Harrington, Evans, and Shelby Foote. "Interview With Shelby Foote." The Mississippi Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 4, 1971, pp. 349–377, p. 359.

- ^ a b "We Could Use a Shelby Foote Today". Theamericanconservative.com. November 29, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Fred L. Schultz, "An interview with Shelby Foote: 'All life has a plot'." Naval History 8.5 (1994): 36–39.

- ^ Judkin Browning. "On Leadership: Heroes and Villains of the First Modern War". Reviews in American History, Volume 45, Number 3, September 2017, p. 442.

- ^ Trudier Harris. "Twenty-First-Century Slavery Or, How to Extend the Confederacy for Two"

- ^ Hidden Treasures: Searching for God in Modern Culture, James M. Wall, Christian Century Foundation, 1997, p. 12

- ^ "Saint Louis Literary Award – Saint Louis University". Slu.edu. Archived from the original on August 23, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ Saint Louis University Library Associates. "Recipients of the Saint Louis Literary Award". Archived from the original on July 31, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ^ Sharrett, Christopher. "Reconciliation and the Politics of Forgetting: Notes on Civil War Documentaries." Cinéaste, vol. 36, no. 4, 2011, pp. 28

- ^ a b Mary A. DeCredico. "Book Review: Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War" Armed Forces & Society 26(2): 2000, 339

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". Achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "W&M Honorary Degree Recipients". wm.edu. The College of William & Mary. September 25, 2020.

- ^ "In Depth with Shelby Foote". C-SPAN.org. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ Reed, John Shelton (2002). The Banner That Won't Stay Furled. Southern Cultures, 8(1), 85.

- ^ Reed, John Shelton (2002). The Banner That Won't Stay Furled. Southern Cultures, 8(1), 88

- ^ "Shelby Foote Dies; Novelist and Historian of Civil War", The Washington Post, June 29, 2005

- ^ Susanna Henighan Potter, Moon Tennessee, 44 (Moon Handbooks, Avalon Travel Publishing, 2009) ISBN 1-59880-114-7

- ^ Coates, Ta-Nehisi (June 13, 2011). "The Convenient Suspension of Disbelief". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ "The Ku Klux Klan Protests as Memphis Renames a City Park - CityLab". Archived from the original on November 12, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ Astor, Maggie. "John Kelly Pins Civil War on a 'Lack of Ability to Compromise'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. October 31, 2017.

- ^ Mitchell, Ellen (October 31, 2017). "White House defends Kelly's Civil War remarks". The Hill.

- ^ "Mississippi Writers Trail markers for Shelby Foote and Walker Percy unveiled in Greenville | Mississippi Development Authority". Mississippi.org. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- ^ "Daniel Craig Based His 'Knives Out' Accent on a Famous Civil War Historian". Cheatsheet.com. March 2, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Crews, Kyle. "An “Unreligious” Affair: (Re) Reading the American Civil War in Foote's Shiloh and Warren's Wilderness." Robert Penn Warren Studies 8.1 (2008): 9+. online

- Grimsley, Mark. "The Greatest Bards: Part 1," The Civil War Monitor 5/18/2020 online

- Meachem, Jon, ed., American Homer: Reflections on Shelby Foote and his Classic The Civil War: A Narrative (Modern Library 2011) table of contents

- Panabaker, James. Shelby Foote and the Art of History: Two Gates to the City (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2004)

- Phillips, Robert L. Shelby Foote: Novelist and Historian (Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2009).

- Sugg, Redding S. and Helen White. Shelby Foote (Twayne Publishers, 1982)

- White, Helen, and Redding S. Sugg. Shelby Foote (Twayne Pub, 1982), focus on novels.

- Williams, Wirt. "Shelby Foote's" Civil War:" The Novelist as Humanistic Historian." The Mississippi Quarterly 24.4 (1971): 429–436.

Primary sources

[edit]- Tolson, Jay, ed. The Correspondence of Shelby Foote and Walker Percy (W.W. Norton Company, 1997).

External links

[edit]- "Shelby Foote Collection" Rhodes College, Memphis

- Shelby Foote Papers Inventory, in the Southern Historical Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill

- PBS Civil War

- American Enterprise interview with Bill Kauffman

- Ole Miss biography and obituary Archived October 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Fellowship of Southern Writers biography

- Reprint of a letter from Foote to William Faulkner, Meridian, Issue 17, University of Virginia

- Shelby Foote Collection (MUM00187) owned by the University of Mississippi.

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Works by or about Shelby Foote at Internet Archive

- Shelby Foote at IMDb

- 1916 births

- 2005 deaths

- 20th-century American Episcopalians

- 20th-century American historians

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- Academics from Memphis, Tennessee

- American male non-fiction writers

- American male novelists

- American military historians

- American military writers

- American people of Austrian-Jewish descent

- Burials at Elmwood Cemetery (Memphis, Tennessee)

- Burials in Tennessee

- Historians from Florida

- Historians of the American Civil War

- Historians of the Southern United States

- Jewish American military personnel

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- Military personnel from Mississippi

- National Humanities Medal recipients

- Neo-Confederates

- Novelists from Alabama

- Novelists from Florida

- Novelists from Mississippi

- Novelists from Tennessee

- People from Greenville, Mississippi

- People from Vicksburg, Mississippi

- 19th-century American writers

- United States Army officers

- United States Army personnel of World War II

- United States Marine Corps personnel of World War II

- Writers from Jackson, Mississippi

- Writers from Memphis, Tennessee

- Writers from Mobile, Alabama

- Writers from Pensacola, Florida