Genocide

| Part of a series on |

| Genocide |

|---|

|

| Issues |

| Related topics |

| Category |

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Genocide is the destruction of a people,[a] either in whole or in part.

Genocide has occurred throughout human history, even during prehistoric times.[1] The Political Instability Task Force estimated that 43 genocides occurred between 1956 and 2016, resulting in about 50 million deaths.[2] The UNHCR estimated that a further 50 million had been displaced by such episodes of violence up to 2008.[2]

In 1948, the United Nations Genocide Convention defined genocide as any of five "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group"; this definition emphasizes intent and excludes cultural genocide as well as crimes targeting political and social groups.[3][4] Raphael Lemkin's original definition of genocide was broader; he focused on genocide as the "destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups", including actions that led to the "disintegration of the political and social institutions, of culture, language, national feelings, religion, and the economic existence of national groups".[5]

The colloquial understanding of genocide is heavily influenced by the Holocaust as its archetype and is conceived as innocent victims targeted for their ethnic identity rather than for any political reason.[6] Genocide is widely considered to be the epitome of human evil[7] and often referred to as the "crime of crimes",[8][9][10] consequently, events are often denounced as genocide.[11]

Origins

Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin coined the term genocide between 1941 and 1943.[12][13] Lemkin's coinage combined the Greek word γένος (genos, "race, people") with the Latin suffix -caedo ("act of killing").[14][15] He submitted the manuscript for his book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe to the publisher in early 1942, and it was published in 1944 as the Holocaust was coming to light outside Europe.[12]

Lemkin's definition of genocide differed from that later adopted by the United Nations in significant ways. He saw genocide as a type of crimes against humanity that could target any type of human collectivity, even one based on a trivial characteristic.[16] He saw genocide as an inherently colonial process, and in his later writings analyzed what he described as the colonial genocides occurring within European overseas territories as well as the Soviet and Nazi empires.[15] Furthermore, his definition of genocidal acts, which was to replace the national pattern of the victim with that of the perpetrator, was much broader than the five types enumerated in the Genocide Convention.[15] Lemkin considered genocide to have occurred since the beginning of human history and dated the efforts to criminalize it to the Spanish critics of colonial excesses Francisco de Vitoria and Bartolomé de Las Casas.[17] The 1946 judgement against Arthur Greiser issued by a Polish court was the first legal verdicts that mentioned the term, using Lemkin's original definition.[18]

Before genocide was made a crime against international law, it was considered a sovereign right.[19] When Lemkin asked about a way to punish the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide, a law professor told him: "Consider the case of a farmer who owns a flock of chickens. He kills them and this is his business. If you interfere, you are trespassing."[20] As late as 1959, many world leaders still "believed states had a right to commit genocide against people within their borders".[19] Lemkin's proposal was more ambitious than simply outlawing this type of mass slaughter. He also thought that the law against genocide could promote more tolerant and pluralistic societies.[15]

Crime

Development

According to the legal instrument used to prosecute defeated German leaders at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, atrocity crimes were only prosecutable by international justice if they were committed as part of an illegal war of aggression. The powers prosecuting the trial were unwilling to restrict a government's actions against its own citizens.[21] In order to criminalize peacetime genocide, Lemkin brought his proposal to criminalize genocide to the newly established United Nations in 1946. He approached the African delegations first in an attempt to build a coalition of smaller states and former colonies that had themselves recently experienced genocide. Lemkin hoped that at this point the major powers—the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union—would step in and take credit for passing the convention.[21]

Opposition to the convention was greater than Lemkin expected due to various countries, and not just great powers, concerned that it would lead their own policies - including treatment of indigenous peoples, European colonialism, racial segregation in the United States, and Soviet nationalities policy - to be labeled genocide. Before the convention was passed, powerful countries (both Western powers and the Soviet Union) secured changes in an attempt to make the convention unenforceable and applicable to their geopolitical rivals' actions but not their own. The result gutted Lemkin's original intentions; he privately considered it a failure.[22] Over the course of these revisions, Lemkin's anti-colonial conception of genocide was transformed into one acceptable to colonial powers.[23] Among the violence freed from the stigma of genocide included the same actions targeting political groups, which the Soviet Union particularly opposed.[citation needed] Although Lemkin credited women's NGOs with securing the passage of the convention, the gendered violence of forced pregnancy, marriage, and divorce was left out.[24] Also excluded from the definition of genocide is the death of large numbers of civilians as collateral damage of military activity such as aerial bombing, even when they make up a significant portion of a nation's population.[25]

International law

After the Holocaust, which was perpetrated by Nazi Germany during World War II, Lemkin successfully campaigned for the universal acceptance of international laws defining and forbidding genocides. In 1946, the first session of the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution that affirmed genocide was a crime under international law and enumerated examples of such events (but did not provide a full legal definition of the crime). In 1948, the UN General Assembly adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG) which defined the crime of genocide for the first time.[26]

The CPPCG was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948[27] and came into effect on 12 January 1951 (Resolution 260 (III)). It contains an internationally recognized definition of genocide which has been incorporated into the national criminal legislation of many countries and was also adopted by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which established the International Criminal Court (ICC). Article II of the Convention defines genocide as:

... any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- (a) Killing members of the group;

- (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

— [28]

Intent

Genocidal acts like murder, forcible transfer of children and forced sterilization are crimes themselves. What makes those crimes genocide is that they are committed with what has been called the "special intent".[29] The special intent, in the terminology of genocide, is similar to the common law concept of specific intent. Antonio Cassese described it as "an aggravated criminal intent that must exist in addition to the criminal intent accompanying the underlying offense".[30] Article II of the CPPCG defines the purpose of committing the acts: "to destroy in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such". The specific intent is a core factor distinguishing genocide from other international crimes, such as war crimes or crimes against humanity.[31]

There is an unresolved "intend debate" over whether specific intent needs to be proven to convict for genocide, or whether a knowledge-based standard should be enough to convict for genocide.[32] Some scholars argue that a knowledge standard would make it easier to obtain convictions. They have argued that intent is too difficult to prove. Those who hold this view believe that causing mass deaths should be enough without any need for a legal requirement to charge a culpable agent for acting with intent.[33]

Some of the existing international tribunal cases like Akayesu and Jelisić have rejected the knowledge standard.[34] The acquittal of Jelisić under the more onerous standard was controversial, and one scholar opined that Nazis would have been allowed to go free under the ICTY's ruling.[35] When Radislav Krstić became the first Serb convicted by the ICTY under the purpose standard, the Krstić court explained that its decision did not rule out a knowledge standard under customary international law.[34]

"In whole or in part"

The phrase "in whole or in part" has been subject to much discussion by scholars of international humanitarian law.[36] In the Ruhashyankiko report of the United Nations it was once argued that the killing of only a single individual could be genocide if the intent to destroy the wider group was found in the murder,[37] yet official court rulings have since contradicted this. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia found in Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Trial Chamber I – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2001) ICTY8 (2 August 2001)[38] that Genocide had been committed. In Prosecutor v. Radislav Krstic – Appeals Chamber – Judgment – IT-98-33 (2004) ICTY 7 (19 April 2004)[39] paragraphs 8, 9, 10, and 11 addressed the issue of in part and found that "the part must be a substantial part of that group. The aim of the Genocide Convention is to prevent the intentional destruction of entire human groups, and the part targeted must be significant enough to have an impact on the group as a whole." The Appeals Chamber goes into details of other cases and the opinions of respected commentators on the Genocide Convention to explain how they came to this conclusion.

The judges continue in paragraph 12, "The determination of when the targeted part is substantial enough to meet this requirement may involve a number of considerations. The numeric size of the targeted part of the group is the necessary and important starting point, though not in all cases the ending point of the inquiry. The number of individuals targeted should be evaluated not only in absolute terms but also in relation to the overall size of the entire group. In addition to the numeric size of the targeted portion, its prominence within the group can be a useful consideration. If a specific part of the group is emblematic of the overall group or is essential to its survival, that may support a finding that the part qualifies as substantial within the meaning of Article 4 [of the Tribunal's Statute]."[40][41]

In paragraph 13 the judges raise the issue of the perpetrators' access to the victims: "The historical examples of genocide also suggest that the area of the perpetrators' activity and control, as well as the possible extent of their reach, should be considered. ... The intent to destroy formed by a perpetrator of genocide will always be limited by the opportunity presented to him. While this factor alone will not indicate whether the targeted group is substantial, it can—in combination with other factors—inform the analysis."[39]

"A national, ethnic, racial or religious group"

The drafters of the CPPCG chose not to include political or social groups among the protected groups. Instead, they opted to focus on "stable" identities, attributes that are historically understood as being born into and unable or unlikely to change over time. This definition conflicts with modern conceptions of race as a social construct rather than innate fact and the practice of changing religion, etc.[42]

International criminal courts have typically applied a mix of objective and subjective markers for determining whether or not a targeted population is a distinct group. Differences in language, physical appearance, religion, and cultural practices are objective criteria that may show that the groups are distinct. However, in circumstances such as the Rwandan genocide, Hutus and Tutsis were often physically indistinguishable.[43]

In such a situation where a definitive answer based on objective markers is not clear, courts have turned to the subjective standard that "if a victim was perceived by a perpetrator as belonging to a protected group, the victim could be considered by the Chamber as a member of the protected group".[44] Stigmatization of the group by the perpetrators through legal measures, such as withholding citizenship, requiring the group to be identified, or isolating them from the whole could show that the perpetrators viewed the victims as a protected group.

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

The convention came into force as international law on 12 January 1951 after the minimum 20 countries became parties. At that time however, only two of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council were parties to the treaty: France and the Republic of China. William Schabas has suggested that a permanent body as recommended by the Whitaker Report to monitor the implementation of the Genocide Convention, and require states to issue reports on their compliance with the convention (such as were incorporated into the United Nations Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture), would make the convention more effective.[45]

UN Security Council Resolution 1674

UN Security Council Resolution 1674, adopted by the United Nations Security Council on 28 April 2006, "reaffirms the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity".[46] The resolution committed the council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict.[47] In 2008 the UN Security Council adopted resolution 1820, which noted that "rape and other forms of sexual violence can constitute war crimes, crimes against humanity or a constitutive act with respect to genocide".[48]

Municipal law

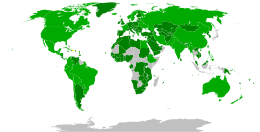

Since the Convention came into effect in January 1951 about 80 United Nations member states have passed legislation that incorporates the provisions of CPPCG into their municipal law.[49]

Prosecutions

The first conviction for genocide in an international court was in 1998 for a perpetrator of the Rwandan genocide. The first head of state to be convicted of genocide was in 2018 for the Cambodian genocide.[13]

Other definitions of genocide

Writing in 1998, Kurt Jonassohn and Karin Björnson stated that the CPPCG was a legal instrument resulting from a diplomatic compromise. As such the wording of the treaty is not intended to be a definition suitable as a research tool, and although it is used for this purpose, as it has international legal credibility that others lack, other genocide definitions have also been proposed. They go on to say that none of these alternative definitions have gained widespread support,[50] they postulate that the major reason why no generally accepted genocide definition has emerged is because academics have adjusted their focus to emphasise different periods and have found it expedient to use slightly different definitions. For example, Frank Chalk and Kurt Jonassohn studied all human history, while Leo Kuper and Rudolph Rummel concentrated on the 20th century, and Helen Fein, Barbara Harff, and Ted Gurr looked at post-World War II events.[50] This has been supported by later scholars.[51][52][53] Rouben Paul Adalian writing in 2002 also highlights the difficulty there has been in trying to develop a common definition for genocide among specialists.[54]

Yehuda Bauer, has argued that the present definition is problematic, contending that many of what are usually called genocides were not racially motivated. Bauer gave the Rwandan Genocide, where, Bauer argued, both the perpetrators and victims were of the same ethnicity, as an example. He argued that, because of this discrepancy, "clearly, the existing definition of genocide is inadequate and needs to be altered."[55]

Cultural genocide and ethnocide

Cultural genocide or culturicide is a concept described by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944, in the same book that coined the term genocide.[56] The destruction of culture was a central component in Lemkin's formulation of genocide.[56] Though the precise definition of cultural genocide remains contested, the United Nations makes it clear that genocide is "the intent to destroy a national, ethnic, racial or religious group... it does not include political groups or so called 'cultural genocide'" and that "Cultural destruction does not suffice, nor does an intention to simply disperse a group" thus this is what "makes the crime of genocide so unique".[57] While the Armenian Genocide Museum defines culturicide as "acts and measures undertaken to destroy nations' or ethnic groups' culture through spiritual, national, and cultural destruction",[58] which appears to be essentially the same as ethnocide. Some ethnologists, such as Robert Jaulin, use the term ethnocide as a substitute for cultural genocide,[59] although this usage has been criticized as risking the confusion between ethnicity and culture.[60] Cultural genocide and ethnocide have in the past been utilized in distinct contexts.[61] Cultural genocide without ethnocide is conceivable when a distinct ethnic identity is kept, but distinct cultural elements are eliminated.[62]

Culturicide involves the eradication and destruction of cultural artifacts, such as books, artworks, and structures.[63] The issue is addressed in multiple international treaties, including the Geneva Conventions and the Rome Statute, which define war crimes associated with the destruction of culture. Cultural genocide may also involve forced assimilation, as well as the suppression of a language or cultural activities that do not conform to the destroyer's notion of what is appropriate.[63] Among many other potential reasons, cultural genocide may be committed for religious motives (e.g., iconoclasm which is based on aniconism); as part of a campaign of ethnic cleansing in an attempt to remove the evidence of a people from a specific locale or history; as part of an effort to implement a Year Zero, in which the past and its associated culture is deleted and history is "reset". The drafters of the 1948 Genocide Convention initially considered using the term, but later dropped it from inclusion.[64][65][66] The term "cultural genocide" has been considered in various draft United Nations declarations, but it is not used by the UN Genocide Convention.[59]Political and social groups

The exclusion of social and political groups as targets of genocide in the CPPCG legal definition has been criticized by some historians and sociologists, for example, M. Hassan Kakar in his book The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982[67] argues that the international definition of genocide is too restricted,[68] and that it should include political groups or any group so defined by the perpetrator and quotes Chalk and Jonassohn: "Genocide is a form of one-sided mass killing in which a state or other authority intends to destroy a group, as that group and membership in it are defined by the perpetrator."[69] In turn some states such as Ethiopia,[70] France,[71] and Spain[72][73] include political groups as legitimate genocide victims in their anti-genocide laws.

Some academics such as Norman Naimark and Anton Weiss-Wendt argue that the exclusion of political and social groups in the final 1948 version of the Genocide Convention was a consequence of Soviet lobbying. Though social and political groups were mentioned in initial drafts of the convention, the Soviet Union would not agree to become a signatory, unless they were omitted.[74][75] The United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect states that the definition of genocide reached in the convention was the "result of a negotiating process and reflects the compromise reached among United Nations Member States."[76]

Harff and Gurr defined genocide as "the promotion and execution of policies by a state or its agents which result in the deaths of a substantial portion of a group ... [when] the victimized groups are defined primarily in terms of their communal characteristics, i.e., ethnicity, religion or nationality".[77] Harff and Gurr also differentiate between genocides and politicides by the characteristics by which members of a group are identified by the state. In genocides, the victimized groups are defined primarily in terms of their communal characteristics, i.e., ethnicity, religion or nationality. In politicides the victim groups are defined primarily in terms of their hierarchical position or political opposition to the regime and dominant groups.[78] Daniel D. Polsby and Don B. Kates Jr. state that "we follow Harff's distinction between genocides and 'pogroms', which she describes as 'short-lived outbursts by mobs, which, although often condoned by authorities, rarely persist'. If the violence persists for long enough, however, Harff argues, the distinction between condonation and complicity collapses."[79][80]

According to Rudolph Rummel, genocide has three different meanings. The ordinary meaning is murder by the government of people due to their national, ethnic, racial, or religious group membership. The legal meaning of genocide refers to the international treaty, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG). This also includes non-killings that in the end eliminate the group, such as preventing births or forcibly transferring children out of the group to another group. A generalized meaning of genocide is similar to the ordinary meaning but also includes government killings of political opponents or otherwise intentional murder. It is to avoid confusion regarding what meaning is intended that Rummel created the term democide to distinguish from this third meaning.[81]

Highlighting the potential for state and non-state actors to commit genocide in the 21st century, for example, in failed states or as non-state actors acquiring weapons of mass destruction, Adrian Gallagher defined genocide as 'When a source of collective power (usually a state) intentionally uses its power base to implement a process of destruction in order to destroy a group (as defined by the perpetrator), in whole or in substantial part, dependent upon relative group size'.[82] The definition upholds the centrality of intent, the multidimensional understanding of destroying, broadens the definition of group identity beyond that of the 1948 definition yet argues that a substantial part of a group has to be destroyed before it can be classified as genocide. Other proposed definitions of genocide include social groups defined by gender, sexual orientation,[83] or gender identity.[84][85]

Criticism of the concept of genocide and alternatives

The concept of genocide has come in for sustained criticism, with some scholars proposing to jettison the concept in favor of alternatives they consider more empirically valid or objectively beneficial.[citation needed] Most civilian killing in the twentieth century were not from genocide, which only applies to select cases.[86][87]

In his 2021 book The Problems of Genocide , historian A. Dirk Moses argued that because of its position as the "crime of crimes", the concept of genocide "blinds us to other types of humanly caused civilian death, like bombing cities and the 'collateral damage' of missile and drone strikes, blockades, and sanctions".[88] Instead, Moses proposes to criminalize "permanent security" - an unobtainable goal of absolute security that if pursued, inevitably leads to anticipatory attacks that harm civilians.[89]

Political scientist Scott Straus puts forward "Mass Categorical Violence", or MCV, in which case the term "genocide" would be its extreme subcategory, with the pinnacle of the genocide subcategory being the "intended total liquidation of a specific population", in which the Holocaust would rank as the "peak of the MCV class and of its genocide subcategory", but at the same time would constitute a category of its own due to its "extraordinary absolute features".[90] American political scientist Rudolph Rummel preferred democide, killing by a government.[91][92][93]

Examples

The concept of genocide can be applied to historical events. The preamble of the CPPCG states that "at all periods of history genocide has inflicted great losses on humanity." Revisionist attempts to challenge or affirm claims of genocide are illegal in some countries. Several European countries ban the denial of the Holocaust and the denial of the Armenian genocide, while in Turkey referring to the Armenian genocide, Greek genocide, and Sayfo, and to the period of mass starvation during the Great Famine of Mount Lebanon affecting Maronites, as genocides may be prosecuted under Article 301.[94]

Historian William Rubinstein argues that the origin of 20th-century genocides can be traced back to the collapse of the elite structure and normal modes of government in parts of Europe following World War I, commenting:

The 'Age of Totalitarianism' included nearly all of the infamous examples of genocide in modern history, headed by the Jewish Holocaust, but also comprising the mass murders and purges of the Communist world, other mass killings carried out by Nazi Germany and its allies, and also the Armenian genocide of 1915. All these slaughters, it is argued here, had a common origin, the collapse of the elite structure and normal modes of government of much of central, eastern and southern Europe as a result of the First World War, without which surely neither Communism nor Fascism would have existed except in the minds of unknown agitators and crackpots.[95]

According to Esther Brito, the way in which states commit genocide has evolved in the 21st century and genocidal campaigns have attempted to circumvent international systems designed to prevent, mitigate, and prosecute genocide by adjusting the duration, intensity, and methodology of the genocide. Brito states that modern genocides often happen on a much longer time scale than traditional ones – taking years or decades – and that instead of traditional methods of beatings and executions less directly fatal tactics are used but with the same effect. Brito described the contemporary plights of the Rohingya and Uyghurs as examples of this newer form of genocide.[96] The abuses against West Papuans in Indonesia have also been described as a slow-motion genocide.[97][98][99][100][101]

Stages, risk factors, and prevention

Study of the risk factors and prevention of genocide was underway before the 1982 International Conference on the Holocaust and Genocide during which multiple papers on the subject were presented.[102] In 1996 Gregory Stanton, the president of Genocide Watch, presented a briefing paper called "The 8 Stages of Genocide" at the United States Department of State.[103] In it he suggested that genocide develops in eight stages that are "predictable but not inexorable".[103][104] The Stanton paper was presented to the State Department, shortly after the Rwandan Genocide and much of its analysis are based on why that genocide occurred. In 2012, he added two additional stages, discrimination and persecution.[105]

Although genocide is often conceived of as a large-scale hate crime motivated by racism instead of political reasons,[6] the Genocide Convention does not require any particular motive for the action. Motives for genocide have also included theft, land grabbing, and revenge.[28]

| Stage | Characteristics | Preventive measures |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Classification |

People are divided into "us and them". | "The main preventive measure at this early stage is to develop universalistic institutions that transcend... divisions." |

| 2. Symbolization |

"When combined with hatred, symbols may be forced upon unwilling members of pariah groups..." | "To combat symbolization, hate symbols can be legally forbidden as can hate speech". |

| 3.

Discrimination |

"Law or cultural power excludes groups from full civil rights: segregation or apartheid laws, denial of voting rights". | "Pass and enforce laws prohibiting discrimination. Full citizenship and voting rights for all groups." |

| 4. Dehumanization |

"One group denies the humanity of the other group. Members of it are equated with animals, vermin, insects, or diseases." | "Local and international leaders should condemn the use of hate speech and make it culturally unacceptable. Leaders who incite genocide should be banned from international travel and have their foreign finances frozen." |

| 5. Organization |

"Genocide is always organized... Special army units or militias are often trained and armed..." | "The U.N. should impose arms embargoes on governments and citizens of countries involved in genocidal massacres, and create commissions to investigate violations" |

| 6. Polarization |

"Hate groups broadcast polarizing propaganda..." | "Prevention may mean security protection for moderate leaders or assistance to human rights groups...Coups d'état by extremists should be opposed by international sanctions." |

| 7. Preparation |

"Victims are identified and separated out because of their ethnic or religious identity..." | "At this stage, a Genocide Emergency must be declared. ..." |

| 8.

Persecution |

"Expropriation, forced displacement, ghettos, concentration camps". | "Direct assistance to victim groups, targeted sanctions against persecutors, mobilization of humanitarian assistance or intervention, protection of refugees." |

| 9. Extermination |

"It is 'extermination' to the killers because they do not believe their victims to be fully human". | "At this stage, only rapid and overwhelming armed intervention can stop genocide. Real safe areas or refugee escape corridors should be established with heavily armed international protection." |

| 10. Denial |

"The perpetrators... deny that they committed any crimes..." | "The response to denial is punishment by an international tribunal or national courts" |

Other authors have focused on the structural conditions leading up to genocide and the psychological and social processes that create an evolution toward genocide. Ervin Staub showed that economic deterioration and political confusion and disorganization were starting points of increasing discrimination and violence in many instances of genocides and mass killing. They lead to scapegoating a group and ideologies that identified that group as an enemy. A history of devaluation of the group that becomes the victim, past violence against the group that becomes the perpetrator leading to psychological wounds, authoritarian cultures and political systems, and the passivity of internal and external witnesses (bystanders) all contribute to the probability that the violence develops into genocide.[106] Intense conflict between groups that is unresolved, becomes intractable and violent can also lead to genocide.[107] In 2006, Dirk Moses criticised genocide studies due to its "rather poor record of ending genocide".[108] Gregory Stanton rejects Moses' critique as a naive expectation for a scholarly discipline, as well as an academic's lack of comprehension of how foreign policy is made.[citation needed]

Genocide recognition

Although in a strict legal sense, genocide is not more severe than other atrocity crimes—crimes against humanity or war crimes—it is often perceived as the "crime of crimes" and grabs attention more effectively than other violations of international law.[109] Consequently, victims of atrocities often label their suffering genocide as an attempt to gain attention to their plight and attract foreign intervention.[110]

See also

Research

Notes

References

- ^ Naimark, Norman M. (2017). Genocide: A World History. Oxford University Press. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-19-976527-0.

- ^ a b Anderton, Charles H.; Brauer, Jurgen, eds. (2016). Economic Aspects of Genocides, Other Mass Atrocities, and Their Prevention. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-937829-6.

- ^ United Nations 2019; Office of the UN Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide 2014; Voice of America 2016

- ^ "art. 2", Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, U.N.T.S., vol. 78, 9 December 1948, p. 277

- ^ Semerdjian 2024, p. 14.

- ^ a b Moses 2023, p. 19.

- ^ Towner 2011, pp. 625–638; Lang 2005, pp. 5–17: "On any ranking of crimes or atrocities, it would be difficult to name an act or event regarded as more heinous. Genocide arguably appears now as the most serious offense in humanity's lengthy—and, we recognize, still growing—list of moral or legal violations."; Gerlach 2010, p. 6: "Genocide is an action-oriented model designed for moral condemnation, prevention, intervention or punishment. In other words, genocide is a normative, action-oriented concept made for the political struggle, but in order to be operational it leads to simplification, with a focus on government policies."; Hollander 2012, pp. 149–189: "... genocide has become the yardstick, the gold standard for identifying and measuring political evil in our times. The label 'genocide' confers moral distinction on its victims and indisputable condemnation on its perpetrators."

- ^ Schabas, William A. (2000). Genocide in International Law: The Crimes of Crimes (PDF) (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 9, 92, 227. ISBN 0-521-78262-7.

- ^ Straus 2022, pp. 223, 240.

- ^ Rugira, Lonzen (20 April 2022). "Why Genocide is "the crime of crimes"". Pan African Review. Archived from the original on 13 June 2024. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Krain, Matthew (September 2012). "J'accuse! Does Naming and Shaming Perpetrators Reduce the Severity of Genocides or Politicides?1: Naming and Shaming Perpetrators". International Studies Quarterly. 56 (3): 574–589. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2012.00732.x.

- ^ a b c Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 7.

- ^ a b Kiernan 2023, p. 2.

- ^ Lemkin 2008, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 14.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 15.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 11.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (2016). "Introduction". Raphael Lemkin and the Concept of Genocide. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-9341-8.

- ^ Goldsmith, Katherine (2010). "The Issue of Intent in the Genocide Convention and Its Effect on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide: Toward a Knowledge-Based Approach". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 5 (3): 238–257. doi:10.3138/gsp.5.3.238.

- ^ a b Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 20.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 22.

- ^ Irvin-Erickson 2023, p. 8.

- ^ a b Moses 2023, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Rubinstein, W. D. (2004). Genocide: A History. London: Pearson Education. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-582-50601-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ Office of the UN Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide 2014.

- ^ a b Kiernan 2023, p. 6.

- ^ Gallagher, Adrian (2013). Genocide and its Threat to Contemporary International Order. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Ambos, Kai (2022). Treatise on International Criminal Law. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-289573-8.

- ^ "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide" (PDF). United Nations. 12 January 1951. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Rodenhäuser, Tilman (2018). Organizing Rebellion: Non-state Armed Groups Under International Humanitarian Law, Human Rights Law, and International Criminal Law. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 284. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198821946.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-882194-6.

- ^ Waller, James (27 May 2016). Confronting Evil: Engaging Our Responsibility to Prevent Genocide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-930072-3.

Indeed, inferring intent from conduct is widely accepted. Of course, there is a higher threshold for concluding that the intent is specifically genocidal, and not merely generally homicidal...The ICTY has even held that the destruction of the cultural existence of a protected group...can be construed as indicators of genocidal intent...Some scholars have gone beyond these court decisions and even argued that as intent is so difficult to prove, we should understand genocide simply as the causing of mass death to defenseless people...rather than merely seeing genocide as the intended action of a coherent agent (in particular, the state), a new generation of scholars is focusing on genocide as an impersonal structural process (including social forces in civil society) that does not necessarily require any intending agent. Here scholars are opening room for larger, longer, and more complicated processes of imperialism and colonialism...Although there is a possibility that moral agency is compromised when we drop intentionality as a defining characteristic of genocide, it is helpful to recognize the ways in which emergent social structures (such as colonization, settlement and civilization) may lead to unintended consequences that look very much like genocide).

- ^ a b Nersessian, David L. (2002). "The Contours of Genocidal Intent: Troubling Jurisprudence from the International Criminal Tribunals". Texas International Law Journal. 37: 231.

- ^ Jensen, Olaf (2013). "Evaluating genocidal intent: the inconsistent perpetrator and the dynamics of killing". Journal of Genocide Research. 15 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/14623528.2012.759396. S2CID 146191450.

- ^ "What is Genocide?". McGill Faculty of Law (McGill University). Archived from the original on 5 May 2007.

- ^ Ruhashyankiko, Nicodème (1978). "Study of the question of the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide". p. 14, paragraph 49–54. Retrieved 27 December 2021 – via Digital Library.

- ^ "Prosecutor v. Dario Kordic & Mario Cerkez – Trial Chamber III – Judgment – en IT-95-14/2 [2001] ICTY 8 (26 February 2001)". worldlii.org.

- ^ a b "The Prosecutor v. Limaj et al. – Decision on Prosecution's Motion to Amend the Amended Indictment – Trial Chamber – en IT-03-66 [2004] ICTY 7 (12 February 2004)". worldlii.org. Archived from the original on 23 August 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ "The Prosecutor v. Limaj et al. – Decision on Prosecution's Motion to Amend the Amended Indictment – Trial Chamber – en IT-03-66 [2004] ICTY 7 (12 February 2004)". worldlii.org. See Paragraph 6: "Article 4 of the Tribunal's Statute, like the Genocide Convention, covers certain acts done with "intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such". Archived from the original on 23 August 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Statute of the International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991, U.N. Doc. S/25704 at 36, annex (1993) and S/25704/Add.1 (1993), adopted by Security Council on 25 May 1993, Resolution 827 (1993).

- ^ Szpak, Agnieszka (2012). "National, Ethnic, Racial, and Religious Groups Protected against Genocide in the Jurisprudence of the ad hoc International Criminal Tribunals". European Journal of International Law. 23 (155): 155–173. doi:10.1093/ejil/chs002.

- ^ Schabas, William A. (2009). Genocide in International Law: The Crime of Crimes (2nd ed.). pp. 124–129.

- ^ Prosecutor v. Bagilishema (Case No. ICTR-95-1A-T), Judgment, 7 June 2001, para. 65.

- ^ Schabas, William A. (2008). War crimes and human rights: essays on the death penalty, justice and accountability. Cameron May. p. 791. ISBN 978-1-905017-63-8 – via Google Books., ISBN 1-905017-63-4

- ^ "Resolution Resolution 1674 (2006)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Security Council passes landmark resolution – world has responsibility to protect people from genocide" (Press release). Oxfam. 28 April 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2010.

- ^ "Security Council Demands Immediate and Complete Halt to Acts of Sexual Violence Against Civilians in Conflict Zones, Unanimously Adopting Resolution 1820 (2008)". United Nations. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ "The Crime of Genocide in Domestic Laws and Penal Codes". Prevent Genocide International.

- ^ a b Jonassohn, Kurt; Björnson, Karin Solveig (1998). Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations in Comparative Perspective: In Comparative Perspective. Transaction Publishers. pp. 133–135. ISBN 0-7658-0417-4 – via Google Books., ISBN 978-0-7658-0417-4

- ^ Bachman, Jeffrey S. (2019). "Introduction: Bringing cultural genocide into the mainstream". Cultural Genocide: Law, Politics, and Global Manifestations. Routledge. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1-351-21410-0.

- ^ Bieńczyk-Missala, Agnieszka (2018). "To act or not to act immediately? Is there really a question?". In Totten, Samuel (ed.). Last Lectures on the Prevention and Intervention of Genocide. Routledge Studies in Genocide and Crimes against Humanity. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-315-40977-1.

- ^ Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (2010). "Editor's Introduction: Changing Themes in the Study of Genocide". In Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–18 [7–8]. ISBN 978-0-19-923211-6.

- ^ Adalian, Rouben Paul (2002). "Finding the Words". In Totten, Samuel; Jacobs, Steven Leonard (eds.). Pioneers of Genocide Studies. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. pp. 3–26 [10–11]. ISBN 978-1-4128-0957-3.

- ^ Bauer, Yehuda (22 January 2023). "Genocide and Genocide Prevention". Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs. 16 (3): 388–403. doi:10.1080/23739770.2022.2163791. ISSN 2373-9770. S2CID 256223657.

- ^ a b Bilsky, Leora; Klagsbrun, Rachel (23 July 2018). "The Return of Cultural Genocide?". European Journal of International Law. 29 (2): 373–396. doi:10.1093/ejil/chy025. ISSN 0938-5428. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect. "The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948)" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Cultural genocide". The Armenian genocide Museum-institute. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ a b Jaulin, Robert (1970). La paix blanche: introduction à l'ethnocide [White Peace: An Introduction to Ethnocide] (in French). Éditions du Seuil.

- ^ Delanty, Gerard; Kumar, Krishan (29 June 2006). The SAGE Handbook of Nations and Nationalism. SAGE Publications. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-4129-0101-7. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

The term 'ethnocide' has in the past been used as a replacement for cultural genocide (Palmer 1992; Smith 1991:30-3), with the obvious risk of confusing ethnicity and culture.

- ^ Bloxham, Donald; Moses, A. Dirk (15 April 2010). The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-0-19-161361-6. Archived from the original on 30 June 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ^ Hall, Thomas D.; Fenelon, James V. (2004). "The futures of indigenous peoples: 9-11 and the trajectory of indigenous survival and resistance". Journal of World-systems Research: 153–197.

- ^ a b "Cultural Genocide, Stolen Lives: The Indigenous Peoples of Canada and the Indian Residential Schools". Facing History and Ourselves. 16 October 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Abtahi, Hirad; Webb, Philippa (2008). The Genocide Convention. BRILL. p. 731. ISBN 978-90-04-17399-6. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Davidson, Lawrence (8 March 2012). Cultural Genocide. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-5344-3. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ See Prosecutor v. Krstic, Case No. IT-98-33-T (Int'l Crim. Trib. Yugo. Trial Chamber 2001), at para. 576.

- ^ Kakar, M. Hassan (1995). Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982. University of California Press.

- ^ Kakar, M. Hassan. "4. The Story of Genocide in Afghanistan: 13. Genocide Throughout the Country". Afghanistan.

- ^ Chalk, Frank; Jonassohn, Kurt (1990). The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04446-1.

- ^ "Court Sentences Mengistu to Death". BBC News. 26 May 2008. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Code Pénal (France); Article 211–1 – génocide" [Penal Code (France); Article 211–1 – genocide] (in French). Prevent Genocide International. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ Daly, Emma (30 June 2003). "Spanish Judge Sends Argentine to Prison on Genocide Charge". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Profile: Judge Baltasar Garzon". BBC News. 7 April 2010. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ Legvold, Robert (1 November 2010). "Stalin's Genocides". Foreign Affairs. No. November/December 2010. ISSN 0015-7120. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Weiss-Wendt, Anton. "The Soviet Union and the Gutting of the UN Genocide Convention". academic.oup.com. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "THE CONVENTION ON THE PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT OF THE CRIME OF GENOCIDE (1948)" (PDF). United Nations. January 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ "What is Genocide?". McGill Faculty of Law. McGill University. Archived from the original on 5 May 2007., source cites Harff, Barbara; Gurr, Ted (1988). "Toward empirical theory of genocides and politicides". International Studies Quarterly. 37 (3).

- ^ Staff. "There are NO Statutes of Limitations on the Crimes of Genocide!". American Patriot Friends Network. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015.. Cites Barbara Harff and Ted Gurr "Toward empirical theory of genocides and politicides", International Studies Quarterly 37, 3 [1988].

- ^ Polsby, Daniel D.; Kates, Don B. Jr. (3 November 1997). "Of Holocausts and Gun Control". Washington University Law Quarterly. 75 (Fall): 1237. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2011. (cites Harff 1992, see other note)

- ^ Harff, Barbara (1992). Fein, Helen (ed.). "Recognizing Genocides and Politicides". Genocide Watch. 27. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press: 37, 38.

- ^ "Democide Verses Genocide: Which is What?". hawaii.edu. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Gallagher, Adrian (2013). Genocide and Its Threat to Contemporary International Order. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 37. ISBN 9781137280268 – via Google Books.

- ^ Feindel, Alycia T. (2005). "Reconciling Sexual Orientation: Creating a Definition of Genocide that Includes Sexual Orientation". Michigan State Journal of International Law. 13 (1–2).

- ^ Park, Andrew (2019). "Yogyakarta Plus 10: A Demand for Recognition of SOGIESC". North Carolina Journal of International Law. 44 (2).

- ^ Isaksson, Hanna (2020). The most controversial crime of international concern? An analysis of gender-based persecution under international criminal law (Master thesis). Örebro University.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 25.

- ^ Graziosi & Sysyn 2022, p. 15.

- ^ Moses 2021, p. 1.

- ^ Moses 2023, pp. 16–17, 27.

- ^ Graziosi & Sysyn 2022, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Harff, Barbara (1996). "Death by Government by R. J. Rummel". The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 27 (1). MIT Press: 117–119. doi:10.2307/206491. JSTOR 206491.

- ^ Harff, Barbara (2017). "The Comparative Analysis of Mass Atrocities and Genocide" (PDF). In Gleditish, N. P. (ed.). R.J. Rummel: An Assessment of His Many Contributions. SpringerBriefs on Pioneers in Science and Practice. Vol. 37. New York: Springer. pp. 111–129. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54463-2_12. ISBN 9783319544632.

- ^ "Democide Verses Genocide: Which is What?". University of Hawaiʻi. Archived from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ "Pair guilty of 'insulting Turkey'". BBC News. 11 October 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ Rubinstein, William (2004). Genocide: A History. London: Pearson Education. p. 7. ISBN 0-582-50601-8 – via Google Books.

- ^ Brito, Esther. "The Changing Face of Genocide: From Mass Death to Mass Trauma". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Jones, Rochelle (22 October 2015). "West Papuan women left isolated and beset by violence under Indonesian rule". The Guardian.

- ^ Webb-Gannon, Camellia; Elmslie, Jim; Kareni, Ronny (27 May 2021). "West Papua is on the verge of another bloody crackdown". The Conversation. University of Wollongong.

- ^ Jed Smith (25 April 2017). "The West Papuan Warriors Are A Rugby League Team Trying To Stop A Genocide". Vice.com.

- ^ NAJ Taylor (19 October 2011). "West Papua: A history of exploitation". Al Jazeera.

- ^ "Slow-motion genocide for West Papua ethnic minorities and Christians". Asianews.it. 9 March 2016.

- ^ Nelson, F. Burton (1989). "'Christian Confrontations with the Holocaust': 1934: Pivotal Year of the Church Struggle". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 4 (3): 283–297 [284]. doi:10.1093/hgs/4.3.283.

- ^ a b Gregory Stanton. The 8 Stages of Genocide, Genocide Watch, 1996

- ^ The FBI has found somewhat similar stages for hate groups.

- ^ Stanton, Gregory (2020). "The Ten Stages of Genocide". Genocide Watch. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020.

- ^ Staub, Ervin (1992). The Roots of Evil: The Origins of Genocide and Other Group Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42214-7 – via Google Books.

- ^ Staub, Ervin (2011). Overcoming Evil: Genocide, Violent Conflict, and Terrorism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538204-4.[page needed]

- ^ Moses, Dirk (22 December 2006). "Why the Discipline of "Genocide Studies" Has Trouble Explaining How Genocides End?". Social Science Research Council. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 22.

- ^ Moses 2023, p. 23.

Bibliography

- Gerlach, Christian (2010). Extremely Violent Societies: Mass Violence in the Twentieth-Century World. Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-139-49351-2 – via Google Books.

- Graziosi, Andrea; Sysyn, Frank E. (2022). "Introduction: Genocide and Mass Categorical Violence". In Graziosi, Andrea; Sysyn, Frank E. (eds.). Genocide: The Power and Problems of a Concept. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-0-2280-0951-1.

- Hollander, Paul (1 July 2012). "Perspectives on Norman Naimark's Stalin's Genocides". Journal of Cold War Studies. 14 (3): 149–189. doi:10.1162/JCWS_a_00250. S2CID 57560838.

- Irvin-Erickson, Douglas (2023). "The history of Rapha'l Lemkin and the UN Genocide Convention". Handbook of Genocide Studies. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 7–26. ISBN 978-1-80037-934-3.

- Kiernan, Ben (2023). "General Editor's Introduction to the Series: Genocide: Its Causes, Components, Connections and Continuing Challenges". The Cambridge World History of Genocide: Volume 1: Genocide in the Ancient, Medieval and Premodern Worlds. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-1-108-49353-6.

- Lang, Berel (2005). "The Evil in Genocide". Genocide and Human Rights: A Philosophical Guide. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 5–17. doi:10.1057/9780230554832_1. ISBN 978-0-230-55483-2.

- Lemkin, Raphael (2008). Axis rule in occupied Europe: laws of occupation, analysis of government, proposals for redress. Clark, New Jersey, USA: Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8.

- Moses, A. Dirk (2021). The Problems of Genocide: Permanent Security and the Language of Transgression. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-02832-5.

- Moses, A. Dirk (2023). "Genocide as a Category Mistake: Permanent Security and Mass Violence Against Civilians". Genocidal Violence: Concepts, Forms, Impact. De Gruyter. pp. 15–38. doi:10.1515/9783110781328-002. ISBN 978-3-11-078132-8.

- Office of the UN Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide (2014). "Legal definition of genocide" (PDF). United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Semerdjian, Elyse (17 July 2024). "Gazafication and Genocide by Attrition in Artsakh/Nagorno Karabakh and the Occupied Palestinian Territories". Journal of Genocide Research: 1–22. doi:10.1080/14623528.2024.2377871.

- Shaw, Martin (2015). What is Genocide?. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-7456-8710-0.

- Straus, Scott (2022). "The Limits of a Genocide Lens and Possible Alternatives". In Graziosi, Andrea; Sysyn, Frank E. (eds.). Genocide: The Power and Problems of a Concept. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 222–256. ISBN 978-0-2280-0951-1.

- Towner, Emil B. (2011). "Quantifying Genocide: What Are We Really Counting (On)?". JAC. 31 (3/4): 625–638. ISSN 2162-5190. JSTOR 41709663.

- United Nations (2019). "Genocide Background". United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- Voice of America (15 March 2016). "What Is Genocide?". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

External links

Documents

- "Voices of the Holocaust". British Library. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) – full text". Genocide Convention.

- "Whitaker Report".

- Stanton, Gregory H. "8 Stages of Genocide" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 November 2021.

Research institutes, advocacy groups, and other organizations

- "Institute for the Study of Genocide".

- "International Association of Genocide Scholars".

- "International Network of Genocide Scholars (INoGS)".

- "United to End Genocide". Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

merger of Save Darfur Coalition and the Genocide Intervention Network

- "Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- "Auschwitz Institute for Peace and Reconciliation".

- "Global Forum Against the Crime of Genocide". Yerevan, Armenia. 12–13 December 2022.

- "Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies". University of Minnesota. 12 December 2023.

- "Genocide Studies Program". Yale University.

- "Montreal Institute for Genocide Studies". Concordia University.

- "Minorities at Risk Project". University of Maryland.

- "Budapest Centre for Mass Atrocities Prevention".