Li Si

Li Si | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left Imperial Chancellor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 246 BC – 208 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarchs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Zhao Gao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | c. 280 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 208 BC (aged 71–72) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Calligrapher, philosopher, politician | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 李斯 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Li Si ([lì sɹ̩́]; c. 280 – 208 BC) was a Chinese calligrapher, philosopher, and politician of the Qin dynasty. He served as Chancellor from 246 to 208 BC, first under King Zheng of the state of Qin—who later became Qin Shi Huang, the "First Emperor" of the Qin dynasty. He then served under Qin Er Shi, Qin Shi Huang's eighteenth son and the second emperor.[1] Concerning administrative methods, Li Si is said to have admired and utilized the ideas of Shen Buhai, repeatedly referring to the technique of Shen Buhai and Han Fei, but regarding law, he followed Shang Yang.[2]

John Knoblock, a translator of classical Chinese texts, considered Li Si to be "one of the two or three most important figures in Chinese history" as a result of his efforts in standardizing the Qin state and its conquered territories. Li Si assisted the Emperor in unifying laws, governmental ordinances, and weights and measures. He also standardized chariots, carts, and characters used in writing, facilitating the cultural unification of China. He "created a government based solely on merit, so that in the empire sons and younger brothers in the imperial clan were not ennobled, but meritorious ministers were", and "pacified the frontier regions by subduing the barbarians to the north and south". He had the metal weapons of the feudal states melted and cast into bells and statues. He also lowered taxes and eased draconian punishments for criminals that had originated from statesman Shang Yang.[3]

Early life

[edit]Li Si was originally from Cai in the state of Chu.[4] As a young man he was a minor functionary in the local administration of Chu. According to the Records of the Great Historian, one day Li Si observed that rats in the outhouse were dirty and hungry, but rats in the barn were well-fed. He suddenly realized that "there is no set standard for honour since everyone's life is different. The values of people are determined by their social status. And like rats, people's social status often depends purely on the random life events around them. And so instead of always being restricted by moral codes, people should do what they deemed best at the moment." He made up his mind to take up politics as a career, which was a common choice for scholars not from a noble family during the Warring States period.

Li Si was unable to advance his career in Chu. He believed that achieving nothing in life while being so intelligent and educated would bring shame to not just himself but to all scholars. After having finished his education with the famous Confucian thinker Xunzi, he moved to the state of Qin, the most powerful state at that time, in an attempt to advance his political career.

Career in Qin

[edit]During his stay in Qin, Li Si became a guest of Lü Buwei, who was Chancellor, and had the chance to talk to King Ying Zheng, who would later become the first emperor of a unified China, Qin Shi Huang. Li Si expressed that the Qin state was extremely powerful, but unifying China was still impossible if all of the other six states at the time united to fight against Qin. Qin Shi Huang was impressed by Li Si's view of how to unify China. Having adopted Li Si's proposal, the ruler of Qin spent generously to lure intellectuals to the state of Qin and sent out assassins to kill important scholars in other states.

In 237 BC, a clique at the Qin court urged King Zheng to expel all foreigners from the state to prevent espionage. As a native of Chu, Li Si would be a target of the policy, so he memorialised[clarification needed] the king explaining the many benefits of foreigners to Qin including "the sultry girls of Zhao."[1] The king relented and, impressed with Li Si's rhetoric, promoted him.[4] The same year, Li Si is reported to have urged King Zheng to annex the neighbouring state of Han to order to intimidate the other five remaining states. Li Si also wrote the Jianzhuke Shu (Petition against the Expulsion of Guest Officers) in 234 BC. Han Fei, a member of the aristocracy from the State of Han, was asked by the Han king to go to Qin and resolve the situation through diplomacy. Li Si, who envied Han Fei's intellect, persuaded the Qin king that he could neither send Han Fei back (as his superior ability would be a threat to Qin) nor employ him (as his loyalty would not be to Qin). As a result, Han Fei was imprisoned, and in 233 BC convinced by Li Si to commit suicide by taking poison. The state of Han was later conquered in 230 BC.

After Qin Shi Huang became emperor, Li Si persuaded him to suppress intellectual dissent.[1] Li Si believed that books regarding things such as medicine, agriculture, and prophecy could be ignored, but political books were dangerous in public hands. He believed that it was hard to make progress and change the country with the opposition of so many "free thinking" scholars. As a result, only the state should keep political books, and only state-run schools should be allowed to educate political scholars. Li Si himself penned the edict ordering the destruction of historical records and literature in 213 BC, including key Confucian texts, which he thought detrimental to the welfare of the state. It is commonly thought that 460 Confucian scholars were buried alive in the well-known "burning of books and burying of scholars".[citation needed]

Death

[edit]When Qin Shi Huang died while away from the capital, Li Si and the chief eunuch Zhao Gao suppressed the late emperor's choice of successor, which was Fusu. At that time, as Fusu was close friends with Meng Tian, there was a high chance that Li Si would be replaced by Meng Tian as chancellor should Fusu become emperor. Fearing a loss of power, Li Si decided to betray the dead Qin Shi Huang. Li Si and Zhao Gao tricked Fusu into committing suicide and installed another prince, Qin Er Shi (229–207 BC), in his place. During the tumultuous aftermath, Zhao Gao convinced the new emperor to install his followers in official positions. When his power base was secure enough, Zhao Gao betrayed Li Si and charged him with treason. Qin Er Shi, who viewed Zhao Gao as his teacher, did not question his decision. Zhao Gao had Li Si tortured until he admitted to the crime and once even intercepted a letter of pleas Li Si had sent to the Emperor. In 208 BC, Zhao Gao had Li Si subjected to the Five Punishments, executed via waist chop at a public market, and his entire family to the third degree exterminated. Sima Qian records Li Si's last words to his son as having been, "I wish that you and I could take our brown dog and go out through the eastern gate of Shang Cai to chase the crafty hare. But how could we do that!"[4]

Legacy

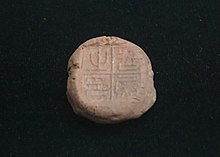

[edit]Believing in a highly bureaucratic system, Li Si was central to the efficiency of Qin and the success of its military conquest. He was also instrumental in systematizing standard measures and currency in post-unified China. He further helped systematize the written Chinese language by promulgating as the imperial standard the small seal script which had already been in use in Qin. In this process, variant glyphs within the Qin script were proscribed, as were variant scripts from the different regions which had been conquered. This had a unifying effect on the Chinese culture for thousands of years.[a][5] Li Si was also the author of the Cangjiepian, the first Chinese language primer of which fragments still exist.[6]

Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Academia Sinica philologist Chen Zhaorong, seal script not only already existed in the E. Zhou period, but was already undergoing a trend toward standardization at that time. Further standardization was carried out by Lĭ Sī and others, and this final standardized form became known to the Hàn people as small seal script.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Sima Qian; Sima Tan (1739) [90s BCE]. "87: Biography of Li Si". Shiji 史記 [Records of the Grand Historian] (in Literary Chinese) (punctuated ed.). Beijing: Imperial Household Department.

- ^ Herrlee G. Creel. Shen Pu-Hai: A Chinese Political Philosopher of the Fourth Century B. C.. pp. 138, 151–152

- ^ Xunzi Volume 1. p. 37. John Knoblock

- ^ a b c Li Si, Chancellor of the Universe in Hammond, Kenneth James (2002). The Human Tradition in Pre-modern China. Scholarly Resources, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8420-2959-9.

- ^ Chen (陳), Zhaorong (昭容) (2003). Research on the Qín (Ch'in) Lineage of Writing: An Examination from the Perspective of the History of Chinese Writing (中央研究院歷史語言研究所專刊) (in Chinese). Academia Sinica, Institute of History and Philology Monograph. ISBN 978-957-671-995-0. pp. 10, 12.

- ^ Outstretched Leaves on his Bamboo Staff: Essays in Honour of Göran Malmqvist on his 70th Birthday, Joakim Enwall, ed., Stockholm: Association of Oriental Studies, 1994, pp. 97–113.

Further reading

[edit]- Bodde, Derk (1967) [1938]. China's First Unifier: a Study of the Ch'In Dynasty as Seen in the Life of Li Ssu (280?-208 B.C.). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. OCLC 605941031.

- Goldin, Paul R. (2005). "Li Si, Chancellor of the Universe". In After Confucius: Studies in Early Chinese Philosophy, pp. 66–75. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Levi, Jean (1993). "Han fei tzu (韓非子)". In Loewe, Michael (ed., 1993). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide, pp. 115–116. (Early China Special Monograph Series No. 2), Society for the Study of Early China, and the Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley, ISBN 978-1-55729-043-4.

- Michael, Franz (1986). China through the Ages: History of a Civilization. pp. 53–67. Westview Press; SMC Publishing, Inc. Taipei. ISBN 978-0-86531-725-3; 957-638-190-8 (ppbk).

- Nivison, David S. (1999). "The Classical Philosophical Writings", pp. 745–812. In Loewe, Michael & Shaughnessy, Edward L. The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC. Cambridge University Press.

- Yap, Joseph P. (2009). Wars With The Xiongnu, A Translation from Zizhi tongjian. AuthorHouse, Bloomington, Indiana, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4. Chapter 1.

- 280s BC births

- 208 BC deaths

- 3rd-century BC Chinese philosophers

- Chinese chancellors

- People executed by the Qin dynasty

- Heads of government who were later imprisoned

- Legalism (Chinese philosophy)

- Qin dynasty calligraphers

- Qin dynasty philosophers

- Qin dynasty government officials

- Qin Shi Huang

- People executed by cutting in half

- Philosophers from Henan

- Philosophers of law

- Politicians from Zhumadian

- Victims of familial execution

- Zhou dynasty philosophers

- Zhou dynasty government officials

- Chinese language reform